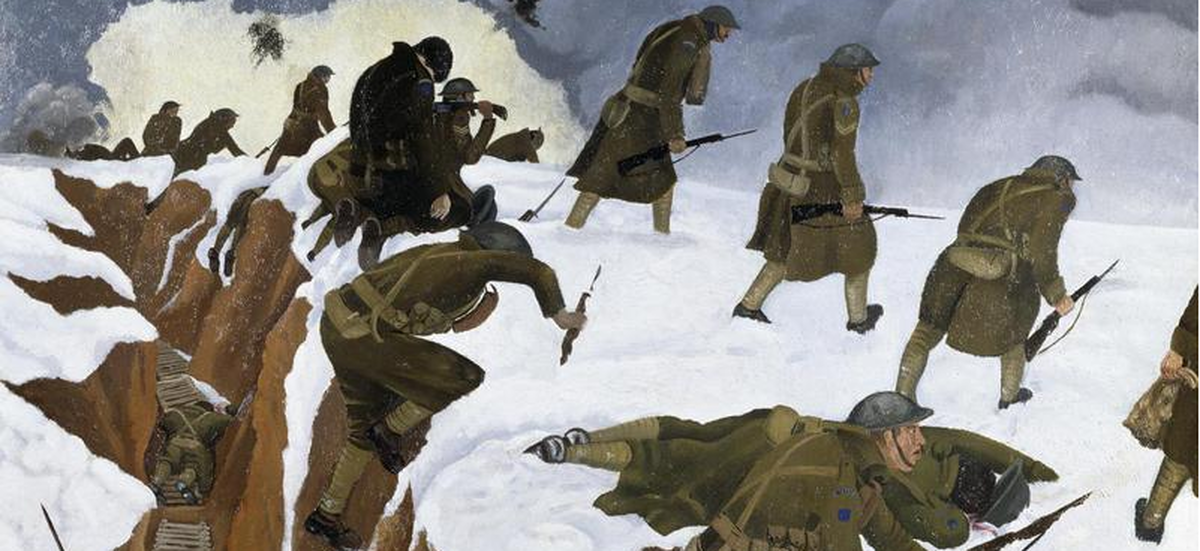

Battle of Menin Road by Septimus Power 1917.

A remarkable number of men appear to have died in England at the beginning of the year. Conscription was introduced in 1916, and perhaps the combination of standards for recruits and for training may have resulted in increased accidents or instances of illness. At least six men died of illness, many of them prior to service overseas. Two men tragically died of accidents. This year also witnessed more fighting in Mesopotamia, Greece, and the dreadful campaigns on the Western Front at Arras and Ypres. The third battle of Ypres, culminating in the Passschendaele actions, claimed far too many lives in the Autumn.

Mesopotamia

The fighting which claimed several lives in the Spring of 1916 returned at the beginning of 1917 as the British captured Baghdad on March 11th. The strategic importance of Kut-el-Amarah related to its location on the confluence of the Shatt-el-Hai and Tigris rivers. The city was captured on on February 24th. Five men from Bedwyn died in Mesopotamia, most of them in the first two months of the year.

Private Bailey 13 January 1917

Henry Charles Bailey was born in Burbage, and he was the son of Charles Bailey and Louisa Underwood of Burbage. His father was born in Marlborough and was described in 1891 as a baker and grocer. His mother was born in Manningford Bruce. They were married in Burbage in 1886, and the bride was living in Milton at that time.

Henry Bailey enlisted in the Wiltshire Regiment in early 1915, and served with the 5th Battalion. The battalion was part of Kitchener’s New Army, and first went overseas to Gallipoli. In January 1916, it was transferred to Mesopotamia, and remained there for the duration of the war.

During the abortive attempts to relieve the siege of Kut in the spring of 1916, Henry Bailey was wounded. His battalion spent the remainder of the year at Amarah, as the new British commander in Mesopotamia, General Maude, concentrated on rebuilding the British army rather than in conducting offensive operations. However in December, the British advanced towards Kut with the ultimate aim of capturing Baghdad.

The men of the 5th battalion moved out of bivouac on January 10th, and their main activity was the creation of the Emperor trench and the extension of the Hai street trench. These trenches were part of a series of saps designed to minimise casualties, and were made in preparation for an assault on Turkish positions on the Hai river. This assault was made on January 25th 1917, and the 5th battalion suffered heavy casualties. However, Henry Bailey died nearly two weeks before this battle, during the construction of these trenches. On the day that he died, his battalion enjoyed a relatively quiet day:

“Improvement of [Emperor] trenches. During night B Coy dug communication trench from Battalion HdQrs to Brigade HdQrs”

There was no fighting, but even so, six men were killed and 23 men were wounded by January 13th. Henry Bailey was one of the 23 wounded. He would have endured a horrendous journey of over 65 miles by boat to Amarah, where several hospitals were located. He may have reached Amarah, or he may have succumbed to his wounds en route.

Henry Bailey is buried in the Amarah War Cemetery, grave XXV. This is a collective grave containing 67 men. He was 24 years old when he died. He is also remembered on the war memorial in Burbage churchyard, and on a brass plaque inside the church.

The fighting which claimed several lives in the Spring of 1916 returned at the beginning of 1917 as the British captured Baghdad on March 11th. The strategic importance of Kut-el-Amarah related to its location on the confluence of the Shatt-el-Hai and Tigris rivers. The city was captured on on February 24th. Five men from Bedwyn died in Mesopotamia, most of them in the first two months of the year.

Private Bailey 13 January 1917

Henry Charles Bailey was born in Burbage, and he was the son of Charles Bailey and Louisa Underwood of Burbage. His father was born in Marlborough and was described in 1891 as a baker and grocer. His mother was born in Manningford Bruce. They were married in Burbage in 1886, and the bride was living in Milton at that time.

Henry Bailey enlisted in the Wiltshire Regiment in early 1915, and served with the 5th Battalion. The battalion was part of Kitchener’s New Army, and first went overseas to Gallipoli. In January 1916, it was transferred to Mesopotamia, and remained there for the duration of the war.

During the abortive attempts to relieve the siege of Kut in the spring of 1916, Henry Bailey was wounded. His battalion spent the remainder of the year at Amarah, as the new British commander in Mesopotamia, General Maude, concentrated on rebuilding the British army rather than in conducting offensive operations. However in December, the British advanced towards Kut with the ultimate aim of capturing Baghdad.

The men of the 5th battalion moved out of bivouac on January 10th, and their main activity was the creation of the Emperor trench and the extension of the Hai street trench. These trenches were part of a series of saps designed to minimise casualties, and were made in preparation for an assault on Turkish positions on the Hai river. This assault was made on January 25th 1917, and the 5th battalion suffered heavy casualties. However, Henry Bailey died nearly two weeks before this battle, during the construction of these trenches. On the day that he died, his battalion enjoyed a relatively quiet day:

“Improvement of [Emperor] trenches. During night B Coy dug communication trench from Battalion HdQrs to Brigade HdQrs”

There was no fighting, but even so, six men were killed and 23 men were wounded by January 13th. Henry Bailey was one of the 23 wounded. He would have endured a horrendous journey of over 65 miles by boat to Amarah, where several hospitals were located. He may have reached Amarah, or he may have succumbed to his wounds en route.

Henry Bailey is buried in the Amarah War Cemetery, grave XXV. This is a collective grave containing 67 men. He was 24 years old when he died. He is also remembered on the war memorial in Burbage churchyard, and on a brass plaque inside the church.

Weymouth

Corporal Scammell 14 January 1917

Maurice Frederick Scammell was born in Shalbourne in 1901, and baptised in April. He was the son of Frederick Scammell and Catherine Noad of 147 Beatrice Street in Swindon. His father was a police constable, and in 1915 he was stationed with the Wiltshire Constabulary in Burbage. In September 1916, he was pensioned due to ill health, and left Burbage to get lighter work in Swindon. Two other sons were in the army, and all of them were in the church choir before they were called up.

Maurice Scammell enlisted with the Wiltshire Regiment, probably at Marlborough. At the time of his death, he was posted to the 3rd Battalion. This battalion was responsible for training men to join other battalions overseas, and also performed home defence duties. His grave registration document records that Maurice Scammell died of accidental injuries. He was fatally injured in a car accident near Bincombe camp:

"On the evening of Sunday January 14th 1917 at about 8:40, Maurice and two companions left the camp walking in the direction of Preston, then a small hamlet, on the north eastern edge of Weymouth. The trio were walking three abreast in a dark unlit road when they heard the sound of a motor horn behind them. His companions jumped to the right, Maurice to the left and straight into the path of the motor car. As was pointed out by one of his companions at the subsequent inquest, Maurice had reacted as if he was still in France"

He was taken to Princess Christian hospital in Weymouth, where he died at 10.00pm. Sadly Maurice Scammell was not the only 16 year to die during the Great War, but he was almost certainly the youngest to enlist from the Bedwyn parishes.

It is curious that he was a corporal at his young age. He attested on May 25th 1915, when he had hardly passed his fourteenth birthday. He must have given a very convincing performance to successfully volunteer at such an age. His mother apparently petitioned for his release from the army. In the absence of any surviving records, it may be assumed that he saw service in France before being recalled to England. The witness evidence at his inquest suggests that this might have been so. The army may have decided that he was out of harm's way at a training camp, and decided to put his skills to use as an instructor, rather than let him go home.

Corporal Scammell 14 January 1917

Maurice Frederick Scammell was born in Shalbourne in 1901, and baptised in April. He was the son of Frederick Scammell and Catherine Noad of 147 Beatrice Street in Swindon. His father was a police constable, and in 1915 he was stationed with the Wiltshire Constabulary in Burbage. In September 1916, he was pensioned due to ill health, and left Burbage to get lighter work in Swindon. Two other sons were in the army, and all of them were in the church choir before they were called up.

Maurice Scammell enlisted with the Wiltshire Regiment, probably at Marlborough. At the time of his death, he was posted to the 3rd Battalion. This battalion was responsible for training men to join other battalions overseas, and also performed home defence duties. His grave registration document records that Maurice Scammell died of accidental injuries. He was fatally injured in a car accident near Bincombe camp:

"On the evening of Sunday January 14th 1917 at about 8:40, Maurice and two companions left the camp walking in the direction of Preston, then a small hamlet, on the north eastern edge of Weymouth. The trio were walking three abreast in a dark unlit road when they heard the sound of a motor horn behind them. His companions jumped to the right, Maurice to the left and straight into the path of the motor car. As was pointed out by one of his companions at the subsequent inquest, Maurice had reacted as if he was still in France"

He was taken to Princess Christian hospital in Weymouth, where he died at 10.00pm. Sadly Maurice Scammell was not the only 16 year to die during the Great War, but he was almost certainly the youngest to enlist from the Bedwyn parishes.

It is curious that he was a corporal at his young age. He attested on May 25th 1915, when he had hardly passed his fourteenth birthday. He must have given a very convincing performance to successfully volunteer at such an age. His mother apparently petitioned for his release from the army. In the absence of any surviving records, it may be assumed that he saw service in France before being recalled to England. The witness evidence at his inquest suggests that this might have been so. The army may have decided that he was out of harm's way at a training camp, and decided to put his skills to use as an instructor, rather than let him go home.

|

Maurice Scammell is buried in Melcombe Regis Cemetery, plot IIIC 2768. He was 16 years of age. The grave has inscribed 'Peace Perfect Peace'. He is also remembered on the war memorial in Burbage churchyard. The Reverend Hubert Sands, vicar of Burbage, wrote of him:

"THE WHOLE VILLAGE will sympathize with Mr and Mrs Scammell in the death of their third son Maurice Scammell, through an accident at Weymouth. He was formerly a server in the choir, and a fine and promising youth. Though under 16, he was Corporal in the 3rd Wilts. May he by the mercy of God rest in peace" [Burbage parish magazine February 1917. Burbage 1914] [ Thank you for contribution of David Gardner who provided much information concerning Maurice Scammell ] |

Mesopotamia

Sergeant Hoare 16 February 1917

William John Hoare was born in Tidcombe, and he was the son of William and Elizabeth Hoare. According to the 1915 Kelly’s Directory, Mrs Elizabeth Hoare was the sub-postmistress at Fosbury post office.

William John Hoare enlisted with the Wiltshire regiment and served in the 5th battalion.

Following the successful battle to capture the Ottoman positions on the Hai river [ 25 January - 4 February 1917], the British captured a second position, known as the Dahra Bend on February 16.

On 16 February the battalion was at the Dahrah bend :

“Battalion relieved and marched back to R19, at 6p.m a thunderstorm of extraordinary violence broke over the camp, huge hailstones descended with great force and in a very short time the whole area was flooded”

There is no indication that William Hoare was killed in action. In the previous days, the battalion had been involved in improving trenches and some 25 men were involved with bombing parties. One man was killed and 32 men were wounded between February 13 and February 16th; William Hoare may have been one of the wounded and may have died either at Amara or during the journey there.

William Hoare was 25 years old when he was killed. He is buried in the Amara War Cemetery, grave 14EC33. He is also remembered on the war memorial in Fosbury.

Private Almond 21 February 1917

Charles Henry Almond was born at Notting Hill Gate, London. His parents were Charles Almond [b1850] and Ann Maria, nee Gilbert [1850 - 1934], and they married in Kensington in 1874. Ann Almond was a widow by 1901, and she was living with her brother, Elijah Gilbert, at 208 Wilton. He was a labourer in the Dodsdown brickworks, and she was a domestic housekeeper. In 1901 and 1911, Charles Almond was a farm labourer in Wilton.

Charles Almond enlisted with the Wiltshire regiment and served in the 5th battalion. His army number was 24604.

Charles Almond was probably wounded before 16th February when the battalion was pulled out of line at the Dahrah bend, and at the time that William John Hoare may have been fatally wounded. In the days preceding his death, the men of the battalion were involved in creating a diversion to deceive the enemy at Shumram:

“20th, 21st and 22nd On River picquet duty. Enemy sniping from direction of Kut. During nights of 21st and 22nd Battn made demonstration at Licorice Factory in order to make enemy believe that a crossing would be attempted from there. The bund was cut it being built up again later and a line of burgees raised, leading towards R19. In addition empty A.T. Carts were led up and down under cover of darkness and planks, bridging material and etc's unloaded and reloaded, a little bridging material being partially hidden just sufficiently to be observed by an enemy aeroplane during daylight. On the night of the 22nd splashing noises were made at the waters edge. From information received from Corps, the enemy was entirely deceived”

Charles Henry Almond was 40 years of age when he died. He was buried at the Shaikh Saad Old Cemetery in 1917, but after the war his grave was lost. In 1933, all of the cemetery headstones were removed as salt in the soils caused great deterioration in the stone. His name is now remembered at the Amara Memorial, Panel 38 XVIII. His name is also on the war memorial at East Grafton churchyard.

The British captured Kut el Amara, the scene of their humiliation in 1916, on 24 February 1917.

Sergeant Hoare 16 February 1917

William John Hoare was born in Tidcombe, and he was the son of William and Elizabeth Hoare. According to the 1915 Kelly’s Directory, Mrs Elizabeth Hoare was the sub-postmistress at Fosbury post office.

William John Hoare enlisted with the Wiltshire regiment and served in the 5th battalion.

Following the successful battle to capture the Ottoman positions on the Hai river [ 25 January - 4 February 1917], the British captured a second position, known as the Dahra Bend on February 16.

On 16 February the battalion was at the Dahrah bend :

“Battalion relieved and marched back to R19, at 6p.m a thunderstorm of extraordinary violence broke over the camp, huge hailstones descended with great force and in a very short time the whole area was flooded”

There is no indication that William Hoare was killed in action. In the previous days, the battalion had been involved in improving trenches and some 25 men were involved with bombing parties. One man was killed and 32 men were wounded between February 13 and February 16th; William Hoare may have been one of the wounded and may have died either at Amara or during the journey there.

William Hoare was 25 years old when he was killed. He is buried in the Amara War Cemetery, grave 14EC33. He is also remembered on the war memorial in Fosbury.

Private Almond 21 February 1917

Charles Henry Almond was born at Notting Hill Gate, London. His parents were Charles Almond [b1850] and Ann Maria, nee Gilbert [1850 - 1934], and they married in Kensington in 1874. Ann Almond was a widow by 1901, and she was living with her brother, Elijah Gilbert, at 208 Wilton. He was a labourer in the Dodsdown brickworks, and she was a domestic housekeeper. In 1901 and 1911, Charles Almond was a farm labourer in Wilton.

Charles Almond enlisted with the Wiltshire regiment and served in the 5th battalion. His army number was 24604.

Charles Almond was probably wounded before 16th February when the battalion was pulled out of line at the Dahrah bend, and at the time that William John Hoare may have been fatally wounded. In the days preceding his death, the men of the battalion were involved in creating a diversion to deceive the enemy at Shumram:

“20th, 21st and 22nd On River picquet duty. Enemy sniping from direction of Kut. During nights of 21st and 22nd Battn made demonstration at Licorice Factory in order to make enemy believe that a crossing would be attempted from there. The bund was cut it being built up again later and a line of burgees raised, leading towards R19. In addition empty A.T. Carts were led up and down under cover of darkness and planks, bridging material and etc's unloaded and reloaded, a little bridging material being partially hidden just sufficiently to be observed by an enemy aeroplane during daylight. On the night of the 22nd splashing noises were made at the waters edge. From information received from Corps, the enemy was entirely deceived”

Charles Henry Almond was 40 years of age when he died. He was buried at the Shaikh Saad Old Cemetery in 1917, but after the war his grave was lost. In 1933, all of the cemetery headstones were removed as salt in the soils caused great deterioration in the stone. His name is now remembered at the Amara Memorial, Panel 38 XVIII. His name is also on the war memorial at East Grafton churchyard.

The British captured Kut el Amara, the scene of their humiliation in 1916, on 24 February 1917.

Ogbourne St. Andrew

Private Angell 22 February 1917

George Angell was born in Ogbourne St. Andrew, and he was the son of George and Rhoda Angell of Ogbourne St. George. The parents were living in Mildenhall parish in 1911. However, George Angell was living with his wife, Elizabeth Sarah Angell, and daughter, Elizabeth Rhoda, at Crabtree cottages near Savernake Lodge. He was employed as a carter on a farm.

He enlisted with the Wiltshire regiment in January 1915, and he served with the 1st battalion. His army number was 18390. In early 1917, he was returned to England, and admitted to Edmonton Military hospital in Middlesex "following an illness brought on from two years of active service at the front". His experience on the Western front would have included the Somme campaign and Ypres. Sadly he did not survive.

Two younger brothers were killed during the war. James Angell was a regular soldier in the 1st battalion, the Wiltshire regiment. He was sadly killed on the Western Front in May 1915.

Robert Angell died of enteric fever in India. He had enlisted with the Royal Garrison Artillery, and was stationed near Poona. He was originally buried in Neemuch cemetery, but he was moved to Kirkee cemetery in 1925. He now has no known grave. Robert died on 19 February 1917, two days before the death of George. It was a heavy price for the Angell family to pay.

“The old Lie; Dulce et Decorum est Pro patria mori” [Wilfred Owen]

Private Angell 22 February 1917

George Angell was born in Ogbourne St. Andrew, and he was the son of George and Rhoda Angell of Ogbourne St. George. The parents were living in Mildenhall parish in 1911. However, George Angell was living with his wife, Elizabeth Sarah Angell, and daughter, Elizabeth Rhoda, at Crabtree cottages near Savernake Lodge. He was employed as a carter on a farm.

He enlisted with the Wiltshire regiment in January 1915, and he served with the 1st battalion. His army number was 18390. In early 1917, he was returned to England, and admitted to Edmonton Military hospital in Middlesex "following an illness brought on from two years of active service at the front". His experience on the Western front would have included the Somme campaign and Ypres. Sadly he did not survive.

Two younger brothers were killed during the war. James Angell was a regular soldier in the 1st battalion, the Wiltshire regiment. He was sadly killed on the Western Front in May 1915.

Robert Angell died of enteric fever in India. He had enlisted with the Royal Garrison Artillery, and was stationed near Poona. He was originally buried in Neemuch cemetery, but he was moved to Kirkee cemetery in 1925. He now has no known grave. Robert died on 19 February 1917, two days before the death of George. It was a heavy price for the Angell family to pay.

“The old Lie; Dulce et Decorum est Pro patria mori” [Wilfred Owen]

George Angell is buried in the churchyard extension of Ogbourne St. Andrew. Prior to his burial, there was a motor funeral entourage from Chilesdon camp. In October 2015, there was a commemorative service, after his grave was discovered in long grass.

His name does not appear on the war memorial at St. Katherine’s church, Savernake, but it does appear on the roll of honour for Mildenhall.

His name does not appear on the war memorial at St. Katherine’s church, Savernake, but it does appear on the roll of honour for Mildenhall.

Cadley

Corporal Manderson 12 March 1917

Laurie Alexander Manderson was born in Brisbane, Australia, in 1881, and he was the the son of James Manderson and Lillias Pringle of North Berwick. His parents married in 1867, and emigrated to Australia on the ship "Royal Dane" in 1869.

After the death of his mother, Laurie Manderson returned to England with his sister Catherine. According to the census records of 1891 and 1901, they lived at Park farm with their maternal grandparents, Thomas and Catherine Pringle. Their father also returned to England, and he died at Park farm between 1891 and 1901.

Laurie Manderson enlisted with the Royal Army Medical Corps, and served with the 327th London Field Ambulance. This was a Home Service field ambulance, which was based in England. His army number was 2057.

In March 1917, Laurie Manderson suffered from illness, diagnosed as Cerebro-spinal meningitis. Several outbreaks of meningitis occurred in barracks during the war. Flexner’s antiserum was distributed from the United States of America by the Rockefeller Foundation, but such medicine either came too late or not at all for Laurie Manderson.

Corporal Manderson 12 March 1917

Laurie Alexander Manderson was born in Brisbane, Australia, in 1881, and he was the the son of James Manderson and Lillias Pringle of North Berwick. His parents married in 1867, and emigrated to Australia on the ship "Royal Dane" in 1869.

After the death of his mother, Laurie Manderson returned to England with his sister Catherine. According to the census records of 1891 and 1901, they lived at Park farm with their maternal grandparents, Thomas and Catherine Pringle. Their father also returned to England, and he died at Park farm between 1891 and 1901.

Laurie Manderson enlisted with the Royal Army Medical Corps, and served with the 327th London Field Ambulance. This was a Home Service field ambulance, which was based in England. His army number was 2057.

In March 1917, Laurie Manderson suffered from illness, diagnosed as Cerebro-spinal meningitis. Several outbreaks of meningitis occurred in barracks during the war. Flexner’s antiserum was distributed from the United States of America by the Rockefeller Foundation, but such medicine either came too late or not at all for Laurie Manderson.

Canterbury

Private New 13 March 1917

Frederick New was born at Grazeley Green, Berkshire, and he was the husband of Lily Adelaide New of Little Bedwyn.

Frederick New probably enlisted with the Wiltshire regiment and was posted to the 4th battalion. Men from this battalion on Home service or deemed medically unfit were transferred to the 85th Provisional battalion or "South Western Brigade Battalion" in April 1915. This battalion moved to Whitstable in Kent in January 1917, after a period at Sandown Park and Seaton Delaval. In Whitstable, it was transferred to the Somerset Light Infantry, and formed the 11th Battalion. Frederick New died in Whitstable, but the cause of his death is unknown.

Private New 13 March 1917

Frederick New was born at Grazeley Green, Berkshire, and he was the husband of Lily Adelaide New of Little Bedwyn.

Frederick New probably enlisted with the Wiltshire regiment and was posted to the 4th battalion. Men from this battalion on Home service or deemed medically unfit were transferred to the 85th Provisional battalion or "South Western Brigade Battalion" in April 1915. This battalion moved to Whitstable in Kent in January 1917, after a period at Sandown Park and Seaton Delaval. In Whitstable, it was transferred to the Somerset Light Infantry, and formed the 11th Battalion. Frederick New died in Whitstable, but the cause of his death is unknown.

He is buried at Canterbury Cemetery, Kent, grave B474. He died at the age of 37 years. His widow chose the following words for his grave: "Gone but not forgotten". He is remembered on the roll of honour at Little Bedwyn.

Froxfield

Private Dobson 22 March 1917

Private Hoare 1st April 1917

Arthur Dobson was the son of Job and Louisa Ann Dobson of 42 The Hill, Froxfield. Job was a roadman, or labourer on District roads. Joseph Frederick Maurice Hoare was the grandson of Harriet Hoare of 1 Blue Lion, otherwise Vine, Cottage, Froxfield. His grandmother was a widow and a laundress in 1911.

The Training Reserve was formed in September 1916 as a result of the Military Service Act, passed in March. Once recruits completed their training, they were posted where ever they were most needed, and not to particular regiments. The following battalions were established at Chiseldon in Wiltshire:

- 92nd 17th (Reserve) Bn, the Royal Warwickshire

- 93rd 15th (Reserve) Bn, the Gloucestershire Regiment

- 94rd 16th (Reserve) Bn, the Gloucestershire Regiment

- 95th 11th (Reserve) Bn, the DCLI

- 96th 16th (Reserve) Bn Portsmouth, the Hampshire Regiment

Arthur Dobson TR7/6595

Joseph Hoare TR7/6587 D Company

It is perhaps significant that Joseph Hoare died only a few days after Arthur Dobson. According to CWGC, Arthur Dobson died of sickness.

Possibly both men were victims of the same ailment. The previous year there had been an outbreak of Scarlet Fever, which had led to the isolation of the camp. In November 1917, the lack of hygiene in parts of the hutted encampment was discussed in parliament. Disease was sadly not unknown to Chiseldon. Other men who also died at the camp at this time are listed below:

- TR7/7374 21 03 1917 Herbert Henry Coward, died of cerebro-spinal meningitis, at 12 noon, admitted hospital on 12th March.

- TR7/7122 21 03 191 Ernest Pickett, died of broncho pneumonia.

- TR7/7127 22 03 1917 John Everall

- TR7/6692 23 03 1917 Percival Fox died of pneumonia.

- TR7/6868 23 03 1917 Leonard Sampson died of cerbro-spinal meningitis.

- TR7/6882 26 03 1917 Alfred James Somerville

- TR7/9850 28 03 1917 Joseph Henry F Purchase

- TR7/9836 29 03 1917 Herbert Alfred Webber

- TR7/7246 30 03 1917 Herbert William Fry

- TR7/13065 31 03 1917 Frank Norman Short

- TR7/7423 01 04 1917 Alfred John Eley died of pneumonia.

- TR7/7393 03 04 1917 Ivan George Day died of illness (measles, broncho-pneumonia)

- TR7/9912 03 04 1917 Joseph Searle Hore

- TR7/10158 05 04 1917 Albert George Gulwell

Arthur Dobson was 18 years old when he died. His name also appears on the war memorial in the churchyard. Joseph Hoare was 18 years old when he died. Both men are buried in Froxfield churchyard.

Mesopotamia

The following two men died in Mesopotamia, and they are both commemorated on Panels 30 and 64 at the Basra memorial. The first panel is for the regiment and the second panel for prisoners of war. They therefore may not not have been killied in action on the date of death.

Private Spanswick 30 March 1917

Frederick Spanswick was the son of George Henry Spanswick and Louisa Alberta Neale Spanswick of 33, Stibb Green, Burbage. His parents married at St. Stephen’s church in Westminster in December 1889. In 1891, his father worked as a plate layer for the Great Western Railway.

He enlisted in the Wiltshire Regiment and served with the 5th battalion. By the end of February, the battalion was 40 miles from Baghdad. On 10th March, the battalion successfully forced a crossing of the Diala, and established a bridgehead. The way to Baghdad was now open and the 5th battalion was the first battalion to enter the city. The author of the war diary describes the fighting of March 29th:

“At 2.30a.m Battalion with first line transport moved forward to rendezvous at Railway Stn. thence along NAHRWAN CANAL to point of assembly in Canal about 3800yds south of enemy's advance position. Patrols sent forward located deep nullah 1400yds north to which the Battalion advanced in good order under shell fire. At 9a.m the Battalion moved forward to the attack and immediately came under heavy enfilade shell Machine Gun and rifle fire. In spite of this, however, the advance pushed forward in masterly style until finally held up about 1300yds from enemy position driving in their advanced troops”

The success of the battalion was not achieved without casualties. There were 28 men killed and 139 men wounded. The following day, the battalion was relieved and returned to bivouac at Daltawa. There are no casualty reports for this day, the recorded date of death for Frederick Spanswick. According to the Burbage parish magazine for April 1917, Frederick Spanswick died of wounds,

Frederick Spanswick was aged 20. He has no known grave and his name is remembered on the Basra Memorial, panel 30 and 64. His name is also on the war memorial in Burbage churchyard.

Private Hillier 12 April 1917

Walter Hillier was born in East Grafton, and he was the son of Frederick (d1939 aged 75) and Fanny Hillier, nee Cox, (d1963 aged 90). His parents married in 1890, and lived in Grafton in 1891. By 1901, they were living in Long Drove, Burbage.

Walter Hillier enlisted with the Wiltshire Regiment and served in the 5th Battalion. His army number was 10041.

On April 11th, the battalion was shelled heavily after a successful brigade attack at Chaliyeh. In the evening, the battalion moved into bivouac as part of Brigade reserve, leaving D Company to support right flank of Cheshires. On April 12th at 16.00, the battalion advanced under heavy shell fire towards Deli Abbas, a village situated right at the foot of the Jabel Hamrin range of hills, and established trenches 2,500 from Turkish positions. The following day, the battalion advanced another 1,00 yards, and 50 casualties were suffered through heat. In the evening, the battalion was relieved by the 7th Gloucesters and retired 4 miles to bivouac.

There are no records of casualties in the regimental war diary for this period. Between the 10th and 14th April, Walter Hillier is the only recorded fatality. It is not known if he was killed or wounded in battle, or a victim of sickness. During the campaign he was mentioned in dispatches.

The following two men died in Mesopotamia, and they are both commemorated on Panels 30 and 64 at the Basra memorial. The first panel is for the regiment and the second panel for prisoners of war. They therefore may not not have been killied in action on the date of death.

Private Spanswick 30 March 1917

Frederick Spanswick was the son of George Henry Spanswick and Louisa Alberta Neale Spanswick of 33, Stibb Green, Burbage. His parents married at St. Stephen’s church in Westminster in December 1889. In 1891, his father worked as a plate layer for the Great Western Railway.

He enlisted in the Wiltshire Regiment and served with the 5th battalion. By the end of February, the battalion was 40 miles from Baghdad. On 10th March, the battalion successfully forced a crossing of the Diala, and established a bridgehead. The way to Baghdad was now open and the 5th battalion was the first battalion to enter the city. The author of the war diary describes the fighting of March 29th:

“At 2.30a.m Battalion with first line transport moved forward to rendezvous at Railway Stn. thence along NAHRWAN CANAL to point of assembly in Canal about 3800yds south of enemy's advance position. Patrols sent forward located deep nullah 1400yds north to which the Battalion advanced in good order under shell fire. At 9a.m the Battalion moved forward to the attack and immediately came under heavy enfilade shell Machine Gun and rifle fire. In spite of this, however, the advance pushed forward in masterly style until finally held up about 1300yds from enemy position driving in their advanced troops”

The success of the battalion was not achieved without casualties. There were 28 men killed and 139 men wounded. The following day, the battalion was relieved and returned to bivouac at Daltawa. There are no casualty reports for this day, the recorded date of death for Frederick Spanswick. According to the Burbage parish magazine for April 1917, Frederick Spanswick died of wounds,

Frederick Spanswick was aged 20. He has no known grave and his name is remembered on the Basra Memorial, panel 30 and 64. His name is also on the war memorial in Burbage churchyard.

Private Hillier 12 April 1917

Walter Hillier was born in East Grafton, and he was the son of Frederick (d1939 aged 75) and Fanny Hillier, nee Cox, (d1963 aged 90). His parents married in 1890, and lived in Grafton in 1891. By 1901, they were living in Long Drove, Burbage.

Walter Hillier enlisted with the Wiltshire Regiment and served in the 5th Battalion. His army number was 10041.

On April 11th, the battalion was shelled heavily after a successful brigade attack at Chaliyeh. In the evening, the battalion moved into bivouac as part of Brigade reserve, leaving D Company to support right flank of Cheshires. On April 12th at 16.00, the battalion advanced under heavy shell fire towards Deli Abbas, a village situated right at the foot of the Jabel Hamrin range of hills, and established trenches 2,500 from Turkish positions. The following day, the battalion advanced another 1,00 yards, and 50 casualties were suffered through heat. In the evening, the battalion was relieved by the 7th Gloucesters and retired 4 miles to bivouac.

There are no records of casualties in the regimental war diary for this period. Between the 10th and 14th April, Walter Hillier is the only recorded fatality. It is not known if he was killed or wounded in battle, or a victim of sickness. During the campaign he was mentioned in dispatches.

Walter Hillier has no known grave, and he is remembered on the Basra Memorial Panel 30 and 64. He was 25 years of age. He is also remembered on the war memorial at Burbage. Inside the church there is a another memorial, a brass plate near the south door.

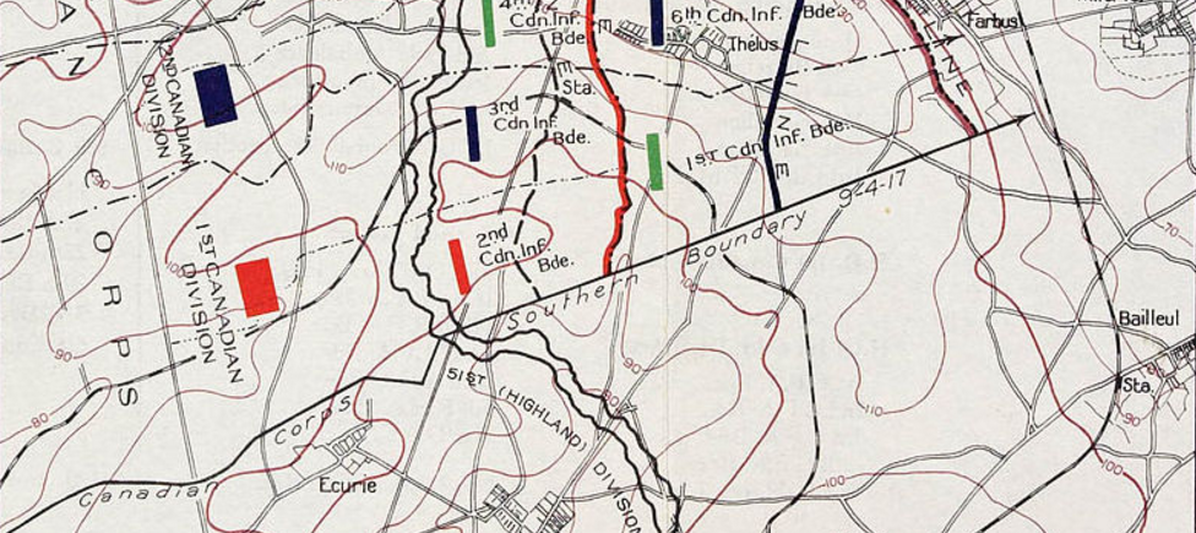

Vimy Ridge

On 9 April 1917, in heavy snow, four Canadian divisions launched what was to be a successful attack on Vimy Ridge. This short but victorious battle illustrated what good planning, effective staff work, and inspirational leadership could achieve. In contrast, the British contribution to what overall became known as the battle of Arras illustrates what could go wrong when leadership and staff work were lacking. As British battalions, such as the Queen’s Westminster Rifles, courageously advanced to their destruction, it became obvious that British military leaders had learned very little from the disastrous battle of the Somme.

Corporal Pearce 1917 9th April 1917

Ernest James Pearce was born in Burbage, and he was the son of Sidney and Sarah Jane Pearce, of 10 Bridewell Street in Devizes.

He enlisted on September 23rd 1914 with the Canadian Infantry Alberta Regiment, and he served with the 10th Battalion. His place of enlistment was Valcartier in Quebec. His listed trade was that of a labourer, and it is assumed that he emigrated to Canada prior to the war. The 10th battalion belonged to the 2nd Brigade in the 1st Canadian Division, and by 1917, this division was one of four which formed the Canadian Corps.

The assault on Vimy ridge began on an Easter Sunday at 05.00. The Canadians advanced behind a tremendous artillery bombardment, through a snow storm, which covered the ground with a thin mantle of white. The 10th battalion advanced to the extreme south of the corp area:

"The 10th Battalion left the "jumping-off" trench immediately the signal was given, and trudged through the muddy shell craters after the barrage, stolidly and imperturbably, indifferent to the bullets which sang and hummed through the shell-smoke like hiving bees. Men crumpled up and fell into the water-filled craters right and left, but the advance continued relentlessly"

The German front line, which was the first objective, was reached at 06.30, and rapidly seized, despite the persistence of enemy machine gun crews and snipers. The mopping up parties encountered trenches blocked with heaps of blood-spattered dead, but collected scores of prisoners.

The advance continued to the second objective with only one surviving officer, which was reached soon after 09.00. The trenches were taken following "messy work with the bayonet and bomb".

On 9 April 1917, in heavy snow, four Canadian divisions launched what was to be a successful attack on Vimy Ridge. This short but victorious battle illustrated what good planning, effective staff work, and inspirational leadership could achieve. In contrast, the British contribution to what overall became known as the battle of Arras illustrates what could go wrong when leadership and staff work were lacking. As British battalions, such as the Queen’s Westminster Rifles, courageously advanced to their destruction, it became obvious that British military leaders had learned very little from the disastrous battle of the Somme.

Corporal Pearce 1917 9th April 1917

Ernest James Pearce was born in Burbage, and he was the son of Sidney and Sarah Jane Pearce, of 10 Bridewell Street in Devizes.

He enlisted on September 23rd 1914 with the Canadian Infantry Alberta Regiment, and he served with the 10th Battalion. His place of enlistment was Valcartier in Quebec. His listed trade was that of a labourer, and it is assumed that he emigrated to Canada prior to the war. The 10th battalion belonged to the 2nd Brigade in the 1st Canadian Division, and by 1917, this division was one of four which formed the Canadian Corps.

The assault on Vimy ridge began on an Easter Sunday at 05.00. The Canadians advanced behind a tremendous artillery bombardment, through a snow storm, which covered the ground with a thin mantle of white. The 10th battalion advanced to the extreme south of the corp area:

"The 10th Battalion left the "jumping-off" trench immediately the signal was given, and trudged through the muddy shell craters after the barrage, stolidly and imperturbably, indifferent to the bullets which sang and hummed through the shell-smoke like hiving bees. Men crumpled up and fell into the water-filled craters right and left, but the advance continued relentlessly"

The German front line, which was the first objective, was reached at 06.30, and rapidly seized, despite the persistence of enemy machine gun crews and snipers. The mopping up parties encountered trenches blocked with heaps of blood-spattered dead, but collected scores of prisoners.

The advance continued to the second objective with only one surviving officer, which was reached soon after 09.00. The trenches were taken following "messy work with the bayonet and bomb".

In contrast to the account of the battle by J.A. Holland, the author of the Story of the Tenth Canadian Battalion 1914 - 1917, the author of the battalion war diary was rather terse in his description of the fighting:

"The two companies in Ecoivres moved into line. The Battalion massing into assembly positions. The enemy artillery was active during this movement. At zero hour the battalion made the attack on the enemy defences, capturing all its objectives, and consolidating them. During the evening the battalion returned to its original frontline and support positions. The weather was unsettled"

The battalion now consolidated the captured trenches, as supporting battalions continued the advance to the ultimate objective, the railway line behind the ridge. The battalion, despite great pride in the taking of Vimy Ridge, had suffered very severely, and the survivors were exhausted. The 10th Battalion suffered 374 casualties, of which 34 men were killed. Sadly Ernest Pearce was one of 34 men killed in the attack.

He is buried in Ecoivres Military Cemetery near Mont St. Eloi, grave VF25. His mother chose the inscription: "He fought the fight . . The Victory won . . And entered into rest". He is remembered in Canada, but not on the war memorial in Burbage.

"The two companies in Ecoivres moved into line. The Battalion massing into assembly positions. The enemy artillery was active during this movement. At zero hour the battalion made the attack on the enemy defences, capturing all its objectives, and consolidating them. During the evening the battalion returned to its original frontline and support positions. The weather was unsettled"

The battalion now consolidated the captured trenches, as supporting battalions continued the advance to the ultimate objective, the railway line behind the ridge. The battalion, despite great pride in the taking of Vimy Ridge, had suffered very severely, and the survivors were exhausted. The 10th Battalion suffered 374 casualties, of which 34 men were killed. Sadly Ernest Pearce was one of 34 men killed in the attack.

He is buried in Ecoivres Military Cemetery near Mont St. Eloi, grave VF25. His mother chose the inscription: "He fought the fight . . The Victory won . . And entered into rest". He is remembered in Canada, but not on the war memorial in Burbage.

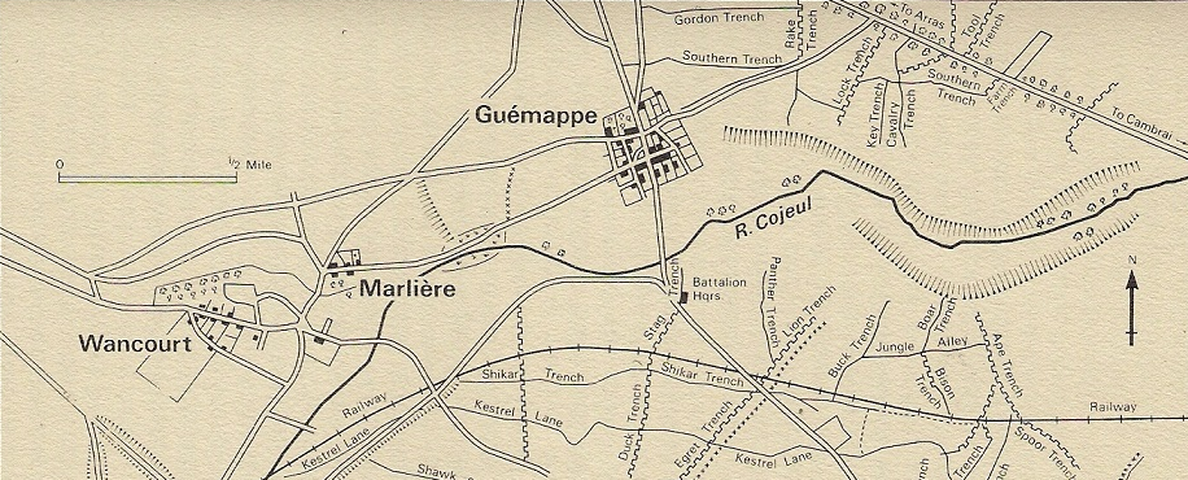

Wancourt

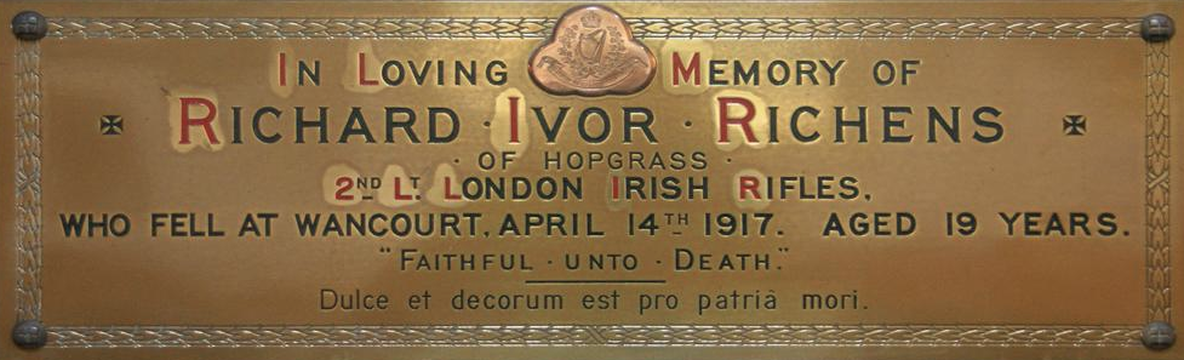

Second Lieutenant Richens 14 April 1917

Richard Ivor Richens was the son of Richard Richens and Bridget Hutchins of Hopgrass farm. His parents first farmed Rudge Manor Farm, Froxfield after their marriage, then took over Hopgrass Farm for many years. His father finally ran Highclose Farm for four years before retirement.

Richard Richens went to Dauntsey’s Agricultural school near Devizes, and immediately joined the army without continuing his education when he was 17 years old. He originally enlisted with the finest of regiments, the Artist Rifles in September 1915. However in April 1916, he was selected for officer training, and subsequently discharged. After training, he was commissioned into the London Irish Rifles, and served with the 18th battalion.

In the Spring of 1917, he was attached to the 16th battalion, Queen’s Westminster Rifles, which was very short of junior officers. This battalion belonged to 169th Brigade in the 56th (London) Division. He served with this battalion for a brief period before his death in action. His commanding officer, Colonel Shoolbred, lamented that he had little or no time to get to know juniors officers such as Richard Richens because they had so recently been attached to his battalion.

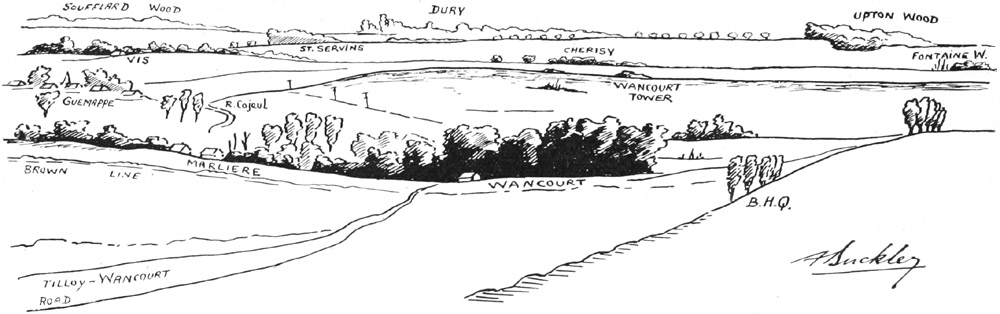

During the battle of Arras ( 9 April - 16 May 1917), the village of Wancourt was captured on 12th April. East of the village, there was a ruined windmill, known as Wancourt Tower, which had been adapted by the Germans as a machine gun and observation post. This windmill and Wancourt Tower ridge were captured by the 50th Division on the 13th April.

Second Lieutenant Richens 14 April 1917

Richard Ivor Richens was the son of Richard Richens and Bridget Hutchins of Hopgrass farm. His parents first farmed Rudge Manor Farm, Froxfield after their marriage, then took over Hopgrass Farm for many years. His father finally ran Highclose Farm for four years before retirement.

Richard Richens went to Dauntsey’s Agricultural school near Devizes, and immediately joined the army without continuing his education when he was 17 years old. He originally enlisted with the finest of regiments, the Artist Rifles in September 1915. However in April 1916, he was selected for officer training, and subsequently discharged. After training, he was commissioned into the London Irish Rifles, and served with the 18th battalion.

In the Spring of 1917, he was attached to the 16th battalion, Queen’s Westminster Rifles, which was very short of junior officers. This battalion belonged to 169th Brigade in the 56th (London) Division. He served with this battalion for a brief period before his death in action. His commanding officer, Colonel Shoolbred, lamented that he had little or no time to get to know juniors officers such as Richard Richens because they had so recently been attached to his battalion.

During the battle of Arras ( 9 April - 16 May 1917), the village of Wancourt was captured on 12th April. East of the village, there was a ruined windmill, known as Wancourt Tower, which had been adapted by the Germans as a machine gun and observation post. This windmill and Wancourt Tower ridge were captured by the 50th Division on the 13th April.

Just before midnight, the 16th battalion received orders to capture the village of Cherisy, 1,000 metres to the east. The attack was to be supported by the 9th battalion Queen Victoria’s Rifles on the left and the 6th battalion, Durham Light Infantry on the right. The author of the battalion history recorded the lack of preparation and sloppy staff work, and stated that "to most of us the enterprise appeared extremely rash":

"The men were exhausted having had one hour's sleep per day over the previous three days. As orders for the attack did not arrive until 11.45pm the night before, no reconnaissance of the ground had been possible nor was there time to explain what was required of the troops"

A creeping barrage had been planned for zero hour, which would move forward at the rate of 100 yards every four minutes. The infantry were to follow at 100 yards nearest distance. However, there was no knowledge of German defensive dispositions, and consequently the supporting artillery bombardment proved ineffective.

The first objective, which was given to A and B companies, was the ridge to the west of Cherisy. The second objective was the village of Cherisy, and this was given to C and D Companies, who would pass through A and B companies after the capture of the ridge.

Early before dawn on April 14th, the 16th battalion moved up from the shelter of the Cojeul Switch, part of the captured Hindenberg Line below Wancourt. The battalion relieved the 5th battalion of the London Rifle Brigade on the ridge. There was an innocent start to a dreadful day:

"It was a beautiful morning and quite bright with the remains of the moon to help the dawning day"

At 05.00 zero hour, the first wave, consisting of Richard Richens with A Company on the right and B Company on the left, advanced in extended order in two lines of men, each line separated by 200 yards. C and D Companies followed at a distance of 300 yards from the second line of the first wave. As soon as the leading companies descended into the valley separating Tower ridge from the first objective, they were met by a murderous machine-gun fire from the front.

German machine gun fire coming from the village of Guémappe cut into A company. The supporting artillery was described by the survivors of the attacking waves as "seeming to be negligible compared to that put down by the enemy". Everything went wrong for the battalion. The village of Guémappe should have been attacked by British troops from 50th Division, but all supporting attacks had already failed or did not take place.

The Germans were soon able to outflank and isolate the two London battalions. Furthermore, the Wancourt Tower Ridge was not wholly occupied by the British. It should have been cleared before any further advance, but there was a gap of 500 yards in the front line between 169th Brigade and 50th Division to the north. Furthermore, part of the ridge was still in German hands, and the survivors of A and B companies received fire from their rear.

A and B companies had reached a series of trenches, which had originally been dug by the Germans to practice bombing, 500 metres below the Wancourt ridge. Within an hour, most of the officers, including Richard Richens, were dead or wounded. Reinforced by survivors from C and D companies, the remnants of the battalion were led by Lieutenant WG Orr of C company, and they held off German counterattacks throughout the morning. The survivors were not able to retire until the early evening. Incredibly, Brigade staff ordered the battalion to hold the isolated trenches in no mans land, and the remarkable Lieutenant Orr led a small band of 15 men who occupied the position throughout the night.

The 16th battalion went into action with 497 men, and it suffered 268 casualties. 96 men were killed or fatally wounded. It should be noted that the action below Wancourt ridge inflicted a total of 629 casualties on the two British battalions; two thirds of the men were lost in a veritable massacre. There were in contrast 49 recorded German casualties. Richard Richens was a platoon commander in A company, and was killed in the first hour of the fighting.

"The men were exhausted having had one hour's sleep per day over the previous three days. As orders for the attack did not arrive until 11.45pm the night before, no reconnaissance of the ground had been possible nor was there time to explain what was required of the troops"

A creeping barrage had been planned for zero hour, which would move forward at the rate of 100 yards every four minutes. The infantry were to follow at 100 yards nearest distance. However, there was no knowledge of German defensive dispositions, and consequently the supporting artillery bombardment proved ineffective.

The first objective, which was given to A and B companies, was the ridge to the west of Cherisy. The second objective was the village of Cherisy, and this was given to C and D Companies, who would pass through A and B companies after the capture of the ridge.

Early before dawn on April 14th, the 16th battalion moved up from the shelter of the Cojeul Switch, part of the captured Hindenberg Line below Wancourt. The battalion relieved the 5th battalion of the London Rifle Brigade on the ridge. There was an innocent start to a dreadful day:

"It was a beautiful morning and quite bright with the remains of the moon to help the dawning day"

At 05.00 zero hour, the first wave, consisting of Richard Richens with A Company on the right and B Company on the left, advanced in extended order in two lines of men, each line separated by 200 yards. C and D Companies followed at a distance of 300 yards from the second line of the first wave. As soon as the leading companies descended into the valley separating Tower ridge from the first objective, they were met by a murderous machine-gun fire from the front.

German machine gun fire coming from the village of Guémappe cut into A company. The supporting artillery was described by the survivors of the attacking waves as "seeming to be negligible compared to that put down by the enemy". Everything went wrong for the battalion. The village of Guémappe should have been attacked by British troops from 50th Division, but all supporting attacks had already failed or did not take place.

The Germans were soon able to outflank and isolate the two London battalions. Furthermore, the Wancourt Tower Ridge was not wholly occupied by the British. It should have been cleared before any further advance, but there was a gap of 500 yards in the front line between 169th Brigade and 50th Division to the north. Furthermore, part of the ridge was still in German hands, and the survivors of A and B companies received fire from their rear.

A and B companies had reached a series of trenches, which had originally been dug by the Germans to practice bombing, 500 metres below the Wancourt ridge. Within an hour, most of the officers, including Richard Richens, were dead or wounded. Reinforced by survivors from C and D companies, the remnants of the battalion were led by Lieutenant WG Orr of C company, and they held off German counterattacks throughout the morning. The survivors were not able to retire until the early evening. Incredibly, Brigade staff ordered the battalion to hold the isolated trenches in no mans land, and the remarkable Lieutenant Orr led a small band of 15 men who occupied the position throughout the night.

The 16th battalion went into action with 497 men, and it suffered 268 casualties. 96 men were killed or fatally wounded. It should be noted that the action below Wancourt ridge inflicted a total of 629 casualties on the two British battalions; two thirds of the men were lost in a veritable massacre. There were in contrast 49 recorded German casualties. Richard Richens was a platoon commander in A company, and was killed in the first hour of the fighting.

Richard Richens was 19 years of age, and he was originally buried at Wancourt Road Cemetery 2, but this cemetery was destroyed by shellfire during the battles of 1918. His grave was lost, and his name is now remembered at London cemetery, Neuville-Vitasse on the Wancourt Memorial 2 Panel 3. He is remembered at Hungerford, where there is a family memorial plaque inside St. Lawrence’s church (above), and also on the war memorial in Bridge Street. He is also remembered at Dauntsey’s school, and on the Artist Rifles roll of honour at Burlington House. Finally his name is recorded on the roll of honour for the Queen’s Westminster Rifles.

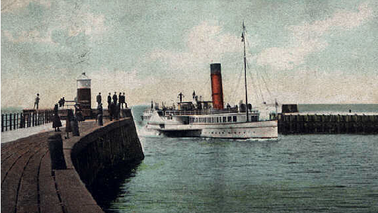

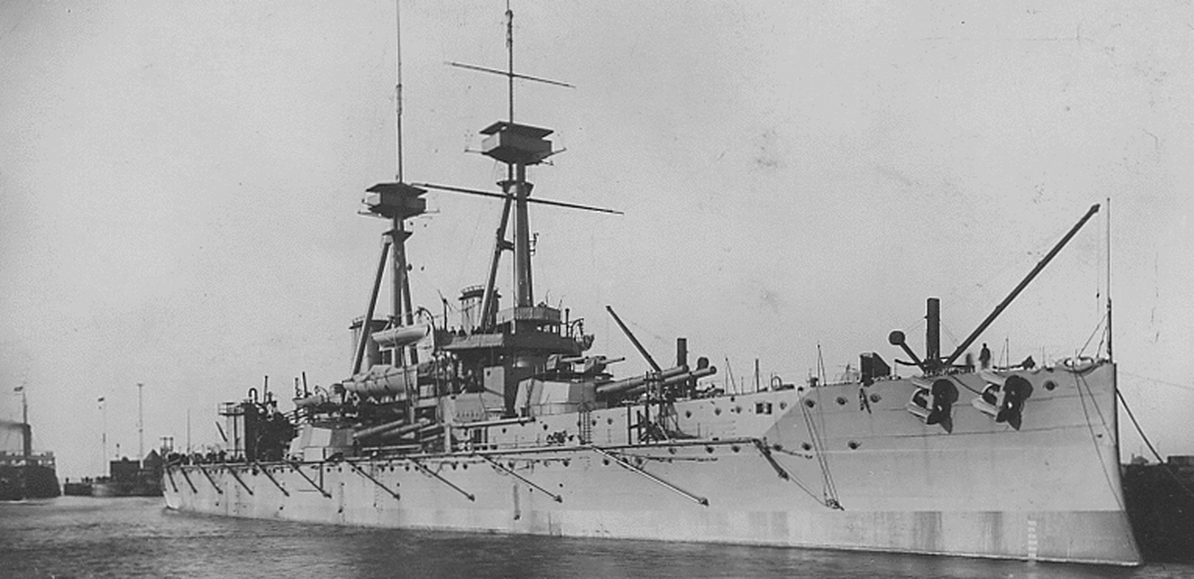

HMPMS Nepaulin

Lieutenant Clark 20 April 1917

James Clark was the son of the Burbage doctor in 1915, Edwin Clark-Jones. In 1907, his father worked in the Royal South Hants and Southampton hospital.

He enlisted with the Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve, and served on HMPMS Nepaulin (His Majesty’s Paddle Mine Sweeper). Nepaulin was built in 1892 as a pleasure boat, and was originally the Clyde paddle steamer Neptune. The steamer carried passengers between the island of Bute and Arran, and served the ports of Greenock and Ayr. The paddle steamer was requisitioned as a minesweeper with a sister ship, Mercury, in 1915, and served as part of the Dover patrol.

On April 20th, the Nepaulin struck a mine three miles offshore of Dunkirk, near the Dyck Light Vessel. The minesweeper sank very quickly. The paddle steamers were known to rapidly fall apart when struck by a mine, and it was essential to abandon ship immediately. However, eighteen lives were lost, including that of James Clark. The mine was laid by U-Boat 12.

Lieutenant Clark 20 April 1917

James Clark was the son of the Burbage doctor in 1915, Edwin Clark-Jones. In 1907, his father worked in the Royal South Hants and Southampton hospital.

He enlisted with the Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve, and served on HMPMS Nepaulin (His Majesty’s Paddle Mine Sweeper). Nepaulin was built in 1892 as a pleasure boat, and was originally the Clyde paddle steamer Neptune. The steamer carried passengers between the island of Bute and Arran, and served the ports of Greenock and Ayr. The paddle steamer was requisitioned as a minesweeper with a sister ship, Mercury, in 1915, and served as part of the Dover patrol.

On April 20th, the Nepaulin struck a mine three miles offshore of Dunkirk, near the Dyck Light Vessel. The minesweeper sank very quickly. The paddle steamers were known to rapidly fall apart when struck by a mine, and it was essential to abandon ship immediately. However, eighteen lives were lost, including that of James Clark. The mine was laid by U-Boat 12.

|

James Clark is remembered on the Portsmouth Naval Memorial, Panel 28. He was 28 years of age. He is also remembered on the roll of honour for the Dover patrol at St. Margaret’s-at-Cliffe near Dover and in a book of remembrance in the St. Margaret’s parish church. His name is recorded on the war memorial in Burbage churchyard.

|

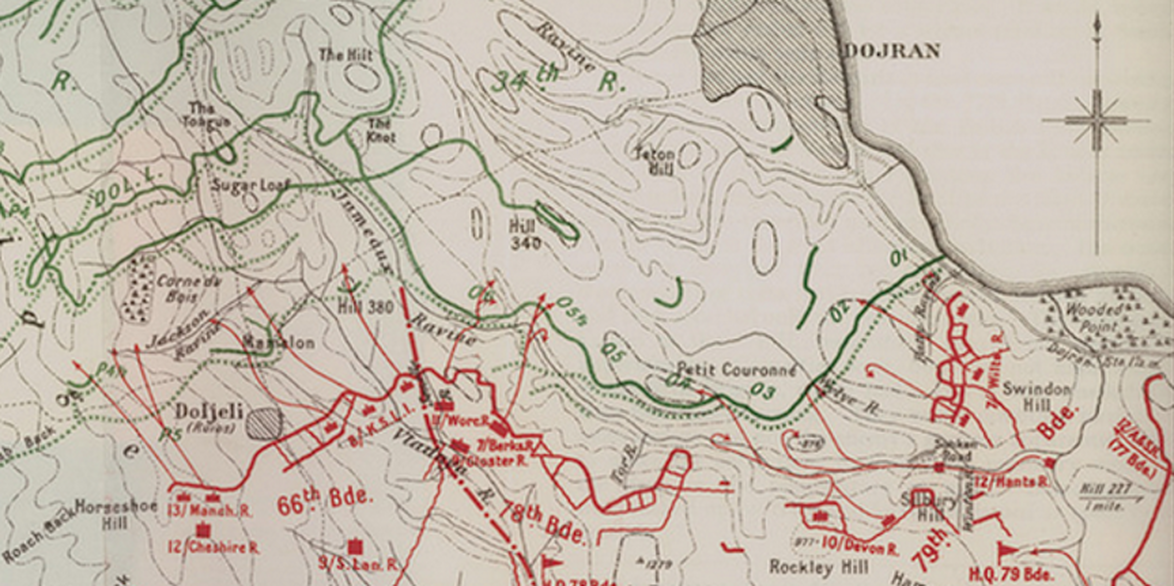

Salonika

The 7th battalion, the Wiltshire regiment was formed at Devizes in September 1914. One year later it was sent to France but in November 1915 it was redeployed to Salonika (Greece) in order to belatedly meet the Bulgarian threat to Serbia. The 7th battalion spent the winter in building roads and defences. In the summer of 1916, it moved to the front line near lake Dorian. In April 1917, a British offensive was launched against the Bulgarians.

The 7th battalion, the Wiltshire regiment was formed at Devizes in September 1914. One year later it was sent to France but in November 1915 it was redeployed to Salonika (Greece) in order to belatedly meet the Bulgarian threat to Serbia. The 7th battalion spent the winter in building roads and defences. In the summer of 1916, it moved to the front line near lake Dorian. In April 1917, a British offensive was launched against the Bulgarians.

April 24 1917: 79th Brigade held the front between Lake Dorian and the Petit Couronné heights. From right to left, the 7th battalion Wiltshire regiment held Swindon Hill, 12 battalion Hampshire regiment the sunken road, and the 10th battalion Devonshire regiment Silbury Hill and Rockley Hill.

Lance Corporal Bull 24 April 1917

Private Doggett 24 April 1917

Private Hunt 24 April 1917

Private Watts 24 April 1917

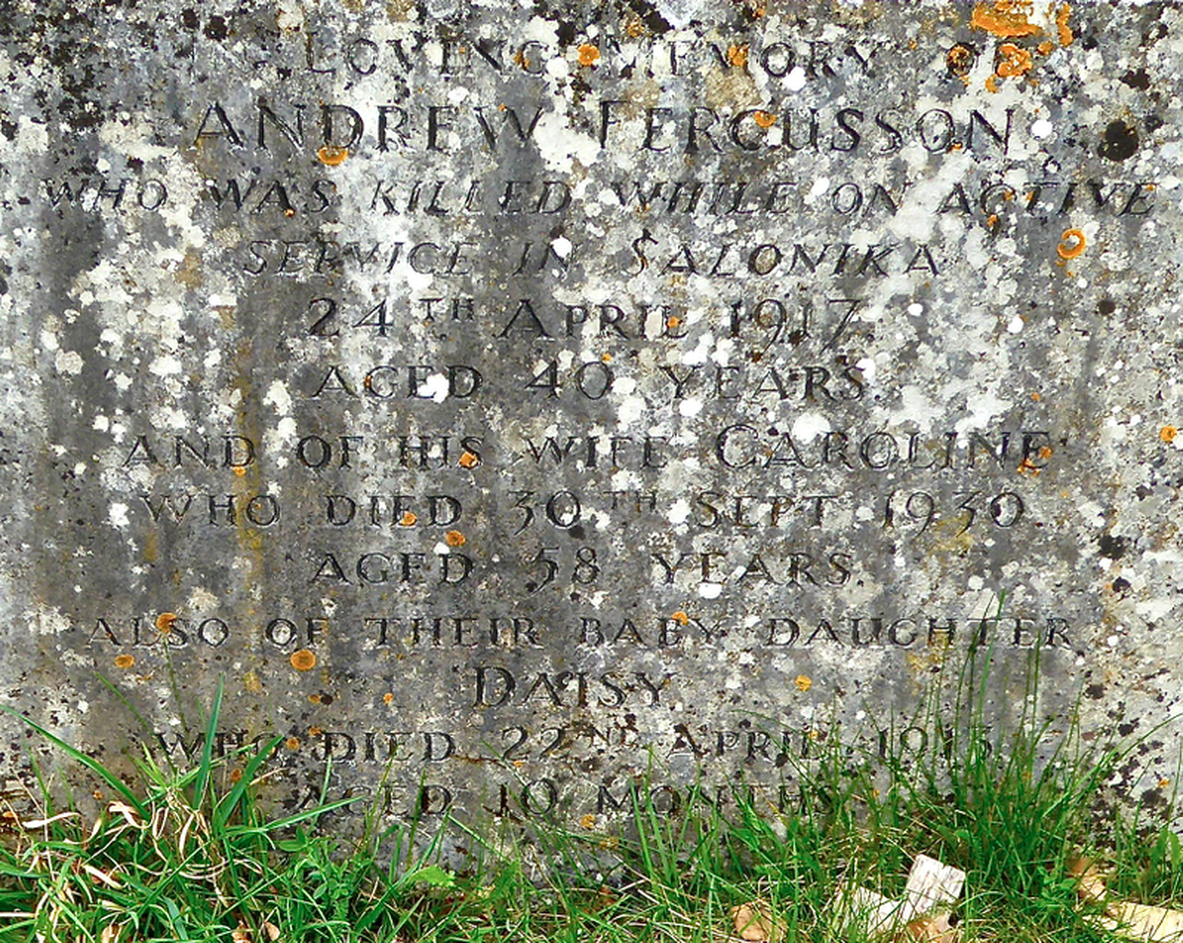

Private Fergusson 25 April 1917

Gerald George Bull was the son of Edgar Theodore and Emma Bull of Overton Delling. His father was the headkeeper, responsible for a rabbit warren on Fyfield down. In 1910, there were over 20 rabbits an acre, and the owner, a race-horse trainer, decided they should be removed:

“Mr. Bull agreed to kill the rabbits in six months and buy the skins and carcases for a pre-arranged price. There were between 13,000 and 14,000 rabbits on the Down and he made a good profit out of the slaughter”

[Wiltshire Archaeological Magazine]

Frederick William Doggett was born in East Grafton, and was the son of James Doggett and Rosa Jackman. His parents had married in 1893, and his father was a retailer, at one time a Grocer, another time the village Postmaster. In 1911, his father was an innkeeper at the Barge Inn, Honey Street Wharf. A 16 year old Frederick Doggett was a carpenter and painter working at the timber yard at the Wharf. A younger brother, Thomas, was also killed during the war.

Frank Frederick Hunt was born in Great Bedwyn, and was the son of Henry and Alice Hunt of 49 Kynaston road in Stoke Newington, London. His father was also born in Great Bedwyn, and in 1871 had been a soldier at Aldershot.

George Richard Watts was the husband of Sarah Jane Watts of 249 East Grafton. She died in 1958 and is buried in East Grafton churchyard with their daughter Phyllis who died in 1956.

Andrew Fergusson was the husband of Caroline Fergusson, and a father of seven children. He was the gamekeeper at Braydon Hook in Savernake Forest before the war.

These five men enlisted in the Wiltshire regiment and served in the 7th battalion. They were all members of A company.

12262 Bull

12249 Doggett

32380 Hunt

18618 Watts

22037 Fergusson

The battalion was sent to France in July 1915, but redeployed to Salonika a few months later in November.

In April 1917, the Allies intended to break through Bulgarian lines around lake Dorian. The 7th battalion was required to capture high ground between the lake and a height called Petit Couronne. The battalion prepared for a night attack, already compromised, on the evening of Tuesday 24th April. The objective was the capture of O1 and O2 trenches.

At 21.05, A company entered Patty Ravine, which lay on the north-west slopes of the Bulgarian trenches. However intensive trench mortar and machine gun fire prevented the bulk of the company from going through the wire:

"Our advance was held up and the company was forced to lie down in shell holes in front of the wire. The main party never got through the wire. A few got into the enemy trenches but were not seen again"

The survivors of the company subsequently withdrew. The battalion strength before the attack was 922 men. Afterwards there were 591 men. The battalion suffered 331 casualties in no more than a few hours of fighting, and 121 of these men were killed. The British trenches after the attack were chaotic:

"Our trenches were by this time full of dead, dying and wounded, all the companies were mixed up. The shelling of our trenches continued and the confusion was such that it was quite impossible to reorganise or make any estimate of losses before daylight"

No further attempt was made to seize the objective, and the early hours of the 25th April were spent with stretcher parties recovering the wounded. The bodies of the Bedwyn men, except Frederick Doggett, were never recovered. Fighting continued into May around lake Dorian but the Bulgarians held their positions.

Lance Corporal Bull 24 April 1917

Private Doggett 24 April 1917

Private Hunt 24 April 1917

Private Watts 24 April 1917

Private Fergusson 25 April 1917

Gerald George Bull was the son of Edgar Theodore and Emma Bull of Overton Delling. His father was the headkeeper, responsible for a rabbit warren on Fyfield down. In 1910, there were over 20 rabbits an acre, and the owner, a race-horse trainer, decided they should be removed:

“Mr. Bull agreed to kill the rabbits in six months and buy the skins and carcases for a pre-arranged price. There were between 13,000 and 14,000 rabbits on the Down and he made a good profit out of the slaughter”

[Wiltshire Archaeological Magazine]

Frederick William Doggett was born in East Grafton, and was the son of James Doggett and Rosa Jackman. His parents had married in 1893, and his father was a retailer, at one time a Grocer, another time the village Postmaster. In 1911, his father was an innkeeper at the Barge Inn, Honey Street Wharf. A 16 year old Frederick Doggett was a carpenter and painter working at the timber yard at the Wharf. A younger brother, Thomas, was also killed during the war.

Frank Frederick Hunt was born in Great Bedwyn, and was the son of Henry and Alice Hunt of 49 Kynaston road in Stoke Newington, London. His father was also born in Great Bedwyn, and in 1871 had been a soldier at Aldershot.

George Richard Watts was the husband of Sarah Jane Watts of 249 East Grafton. She died in 1958 and is buried in East Grafton churchyard with their daughter Phyllis who died in 1956.

Andrew Fergusson was the husband of Caroline Fergusson, and a father of seven children. He was the gamekeeper at Braydon Hook in Savernake Forest before the war.

These five men enlisted in the Wiltshire regiment and served in the 7th battalion. They were all members of A company.

12262 Bull

12249 Doggett

32380 Hunt

18618 Watts

22037 Fergusson

The battalion was sent to France in July 1915, but redeployed to Salonika a few months later in November.

In April 1917, the Allies intended to break through Bulgarian lines around lake Dorian. The 7th battalion was required to capture high ground between the lake and a height called Petit Couronne. The battalion prepared for a night attack, already compromised, on the evening of Tuesday 24th April. The objective was the capture of O1 and O2 trenches.

At 21.05, A company entered Patty Ravine, which lay on the north-west slopes of the Bulgarian trenches. However intensive trench mortar and machine gun fire prevented the bulk of the company from going through the wire:

"Our advance was held up and the company was forced to lie down in shell holes in front of the wire. The main party never got through the wire. A few got into the enemy trenches but were not seen again"

The survivors of the company subsequently withdrew. The battalion strength before the attack was 922 men. Afterwards there were 591 men. The battalion suffered 331 casualties in no more than a few hours of fighting, and 121 of these men were killed. The British trenches after the attack were chaotic:

"Our trenches were by this time full of dead, dying and wounded, all the companies were mixed up. The shelling of our trenches continued and the confusion was such that it was quite impossible to reorganise or make any estimate of losses before daylight"

No further attempt was made to seize the objective, and the early hours of the 25th April were spent with stretcher parties recovering the wounded. The bodies of the Bedwyn men, except Frederick Doggett, were never recovered. Fighting continued into May around lake Dorian but the Bulgarians held their positions.

|

The names of the five men are remembered on the Doiran Memorial.

Gerald Bull was aged 31. His name is on the war memorial in Great Bedwyn churchyard. Frederick Doggett is buried in the Doiran Military cemetery, grave IA7. He was aged 22. His name also appears on the war memorial at Stanton St.Bernard Church, and also at Woodborough. Frank Hunt was aged 22. His name is on the war memorial in Great Bedwyn churchyard. George Watts was aged 39. His name is on the war memorial in East Grafton churchyard. Andrew Fergusson was aged 40. His name is on the roll of honour formerly in Christchurch Cadley, and now St. Mary’s church, Marlborough. His name is also on the gravestone in Cadley churchyard belonging to his wife, who died in 1930, and their youngest daughter, Daisy, who died in 1913 at 10 months. |

Oppy Wood

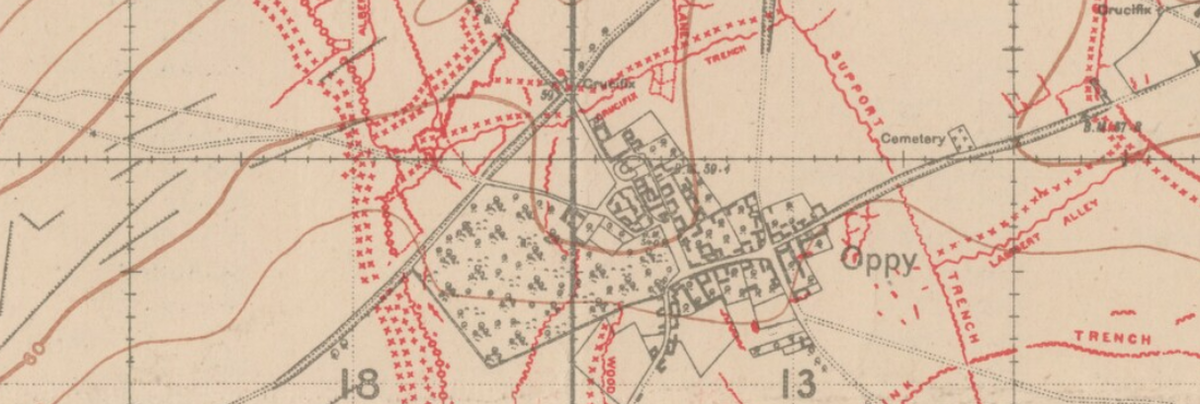

The village of Oppy, its southern neighbour Gavrelle, and its northern neighbour Arleux, lay east of Arras, and far behind the German frontline. However in March 1917, the Germans withdrew to the formidable Hindenburg line, and these villages were incorporated into their new frontline. On April 23rd, the British captured part of Gavrelles. A second operation was planned for April 28th, and three divisions were tasked with the capture of the three villages:

The village of Oppy, its southern neighbour Gavrelle, and its northern neighbour Arleux, lay east of Arras, and far behind the German frontline. However in March 1917, the Germans withdrew to the formidable Hindenburg line, and these villages were incorporated into their new frontline. On April 23rd, the British captured part of Gavrelles. A second operation was planned for April 28th, and three divisions were tasked with the capture of the three villages:

- Gavrelles, 63rd Royal Naval Division

- Oppy, 2nd Division

- Arleux, 1st Canadian Division

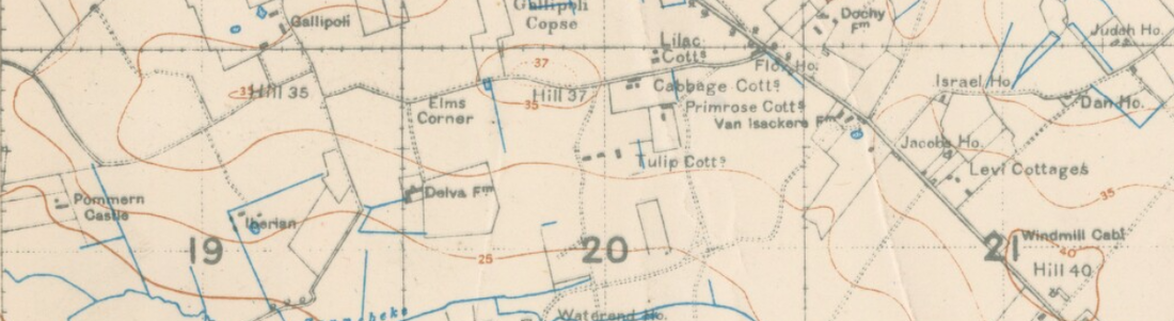

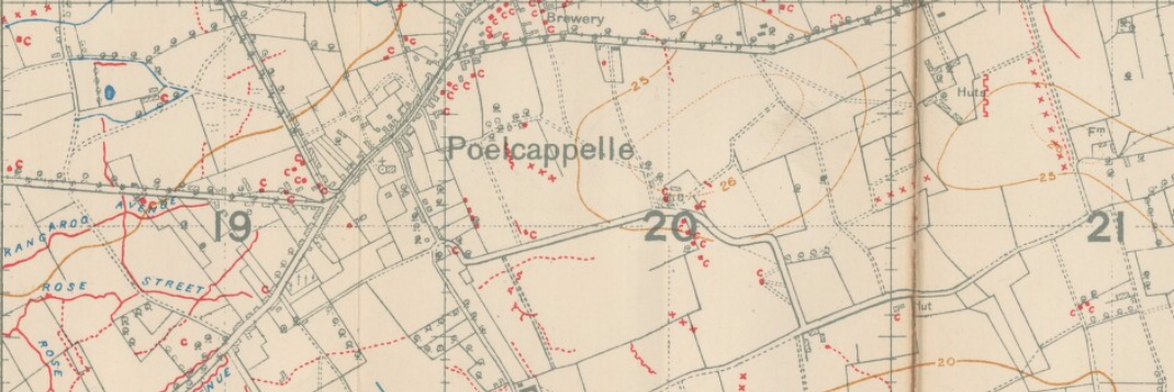

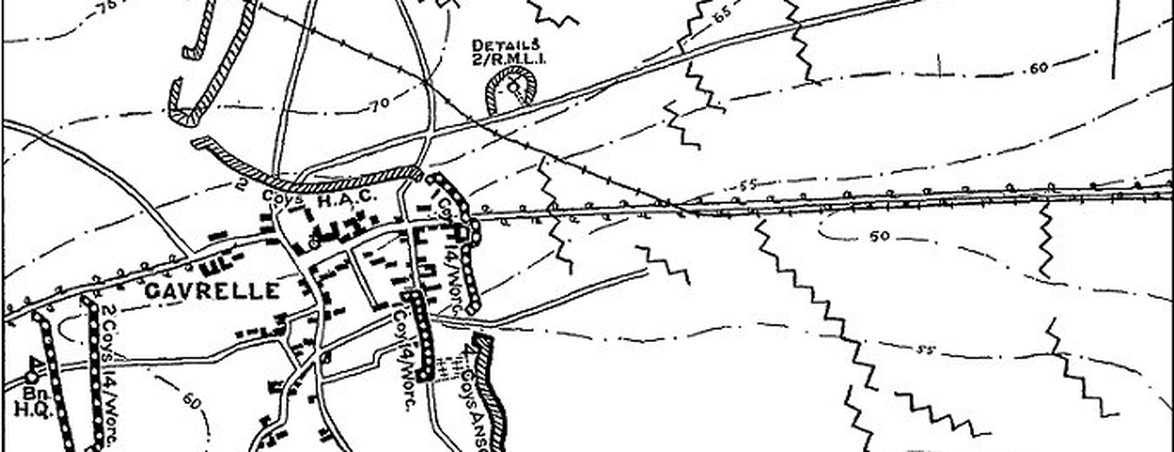

NLS 51B NW 1:20,000 Oppy Wood May 1917.

NLS 51B NW 1:20,000 Oppy Wood May 1917.

Lance Corporal Gigg 28 April 1917

John Lewis Gigg was the son of Charles and Sarah Gigg of 67 Brook Street in Great Bedwyn. He enlisted as a regular soldier with the Royal Berkshire Regiment in September 1913. He served with the 1st battalion.

In April 1917, his battalion was part of 99 Brigade in the 2nd Division which was tasked with the capture of Oppy. On the day that John Gigg died, most of the battalion was held in reserve. although a small group of 20 men were detached to assist 100th Field Ambulance in the evacuation of wounded. In the evening, the battalion received a warning order to prepare an attack to the right of Oppy wood, but that attack was postponed until the early hours of April 29th.

The fate of John Gigg may have been decided by the transfer of D company to the 1st battalion, King’s Royal Rifle Corps at 02.00 on April 28th. This battalion was significantly under strength; 50 men had recently been temporarily detached, leaving only 325 men. Reinforced with D company, the 1st battalion, King’s Royal Rifle Corps launched an unsuccessful attack , and incurred a large number of casualties. D company also suffered severe casualties. The 1st battalion Royal Berkshire Regiment, suffered two fatalities on April 28th. John Gigg was one of them and he may have been part of D company.

The following day, 1st battalion Royal Berkshire Regiment launched an attack at Oppy wood. The operation was a failure despite the bravery of the men, particularly a Lance Corporal Welch who was awarded the Victoria Cross. The casualties were severe: 18 men killed, 19 men wounded, and 89 men missing. Out of a total strength of 250 men, there were 151 casualties. It is ironic that the battalion was expected to launch an attack having recently surrendered D company to another battalion. However, all three battalions in 99 Brigade were seriously understrength, and amounted to less than one battalion in total. This situation begs the question why men's lives were squandered in piecemeal attacks which seemed to have little chance of success. With better senior leadership, John Gigg and his colleagues might have survived to fight another day.

John Gigg has no known grave. He is remembered on the Arras Memorial Bay 7. His name is also on the war memorial in Great Bedwyn churchyard.

Private Newman 28 April 1917

William Newman was the son of Mrs Eliza Ann Newman, of East Sands in Burbage.

William Newman enlisted with the Royal Marine Light Infantry at Portsmouth, and served with the 2nd Battalion. He was part of 188 Brigade in the 63 Royal Naval Division. This division was formed in 1914 from a surplus of naval recruits, and it enjoyed a very high reputation throughout the war.

On April 28th, the two Marine battalions of 188 Brigade, supported by C company from the Anson battalion, were ordered to seize ground east of the village of Gavrelles. The 1st battalion Royal Marine Light Infantry was tasked with an advance due east from north of the village to seize a line of German trenches. The 2nd battalion Royal Marine Light Infantry, supported on the left by C company from Anson battalion were tasked with an advance north eastwards to capture Gavrelles windmill and to link up with the 1st battalion east of the village.

John Lewis Gigg was the son of Charles and Sarah Gigg of 67 Brook Street in Great Bedwyn. He enlisted as a regular soldier with the Royal Berkshire Regiment in September 1913. He served with the 1st battalion.

In April 1917, his battalion was part of 99 Brigade in the 2nd Division which was tasked with the capture of Oppy. On the day that John Gigg died, most of the battalion was held in reserve. although a small group of 20 men were detached to assist 100th Field Ambulance in the evacuation of wounded. In the evening, the battalion received a warning order to prepare an attack to the right of Oppy wood, but that attack was postponed until the early hours of April 29th.

The fate of John Gigg may have been decided by the transfer of D company to the 1st battalion, King’s Royal Rifle Corps at 02.00 on April 28th. This battalion was significantly under strength; 50 men had recently been temporarily detached, leaving only 325 men. Reinforced with D company, the 1st battalion, King’s Royal Rifle Corps launched an unsuccessful attack , and incurred a large number of casualties. D company also suffered severe casualties. The 1st battalion Royal Berkshire Regiment, suffered two fatalities on April 28th. John Gigg was one of them and he may have been part of D company.

The following day, 1st battalion Royal Berkshire Regiment launched an attack at Oppy wood. The operation was a failure despite the bravery of the men, particularly a Lance Corporal Welch who was awarded the Victoria Cross. The casualties were severe: 18 men killed, 19 men wounded, and 89 men missing. Out of a total strength of 250 men, there were 151 casualties. It is ironic that the battalion was expected to launch an attack having recently surrendered D company to another battalion. However, all three battalions in 99 Brigade were seriously understrength, and amounted to less than one battalion in total. This situation begs the question why men's lives were squandered in piecemeal attacks which seemed to have little chance of success. With better senior leadership, John Gigg and his colleagues might have survived to fight another day.

John Gigg has no known grave. He is remembered on the Arras Memorial Bay 7. His name is also on the war memorial in Great Bedwyn churchyard.

Private Newman 28 April 1917

William Newman was the son of Mrs Eliza Ann Newman, of East Sands in Burbage.

William Newman enlisted with the Royal Marine Light Infantry at Portsmouth, and served with the 2nd Battalion. He was part of 188 Brigade in the 63 Royal Naval Division. This division was formed in 1914 from a surplus of naval recruits, and it enjoyed a very high reputation throughout the war.

On April 28th, the two Marine battalions of 188 Brigade, supported by C company from the Anson battalion, were ordered to seize ground east of the village of Gavrelles. The 1st battalion Royal Marine Light Infantry was tasked with an advance due east from north of the village to seize a line of German trenches. The 2nd battalion Royal Marine Light Infantry, supported on the left by C company from Anson battalion were tasked with an advance north eastwards to capture Gavrelles windmill and to link up with the 1st battalion east of the village.

Situation at Gavrelle 29th April. Village was held by remainder of Anson battalion and by HAC. The 14 battalion Warwickshire regiment was brought up to support the defence of the village.

Situation at Gavrelle 29th April. Village was held by remainder of Anson battalion and by HAC. The 14 battalion Warwickshire regiment was brought up to support the defence of the village.

The windmill was captured but the 2nd battalion suffered from increasing machine gun fire and sniping. By 07.30, all objectives were taken but at great cost. Furthermore the left flank of the battalion remained exposed as the 1st battalion attack had failed completely, and C company from Anson battalion had run into troubles of their own. By 10.00, the 2nd battalion was isolated, and subjected to increasing German counter attacks. In the early afternoon, the survivors of the battalion were surrounded, and many were seen to surrender. The casualties in the battalion, 494 men, were very severe: 166 men killed, 152 men wounded, and 176 taken prisoner. It was a disaster unprecedented in the history of the Royal Naval Division.

Both John Gigg and William Newman died in a battle, probably no more than several 1,000 meters from each other, and probably within a few hours of each other's death. Neither of them have a known grave. William Newman is remembered on Arras Memorial Bay 1. There is no local memorial.

Both John Gigg and William Newman died in a battle, probably no more than several 1,000 meters from each other, and probably within a few hours of each other's death. Neither of them have a known grave. William Newman is remembered on Arras Memorial Bay 1. There is no local memorial.

Cherisy

Regimental Sergeant Major Bartholomew 8th May 1917

Henry James Bartholomew was born in Great Bedwyn in 1879. His parents, Francis and Susan Bartholomew, lived on Bedwyn common, and his father worked as a woodman. The family later moved to Church Street in Great Bedwyn, and then Newtown.

Henry Bartholomew, a farm labourer, enlisted in 1898 with the Royal Berkshire Regiment and served in the 1st battalion. He served in Africa and Gibralter. In 1905, he left the army as a sergeant but went on the reserve list. He married Florence Minnie Roles in 1907, and the couple lived in Southampton, where he was a member of the Southampton Police Force. In 1910, he re-engaged with the reserve as a sergeant, but was discharged in May 1914.

In August 1914 he enlisted again with the Royal Berkshire regiment, and served in the 6th (Service) battalion. His army number was 10298. He embarked for France with the battalion on 25th July 1915. He was promoted to Regimental Sergeant major on 18th July 1915, and he was awarded the DCM on July 1st 1916.

On the day that he died, the battalion was on the frontline at Cherisy, where Richard Richens had lost his life a few days earlier. The terse war diary entry records that there was considerable shelling all day, and it was that shelling that took Henry Bartholomew’s life. His widow later received a letter which stated:

“Rest assured that he suffered no pain, being killed instantaneously with three others by a Hun shell. You may be comforted in the knowledge that he was a good soldier, friend, and comrade, and a brave man”

Apparently he was standing outside a dugout, supervising the issue of rations when the shell landed. The citation of his DCM reveals that he had died as he had lived:

"For conspicuous gallantry during operations, when he organised and maintained a constant supply of ammunition and bombs, and on many occasions went fearlessly through the enemy’s barrage, utterly indifferent to personal danger"

He was aged 37 years, and he is buried in the London Cemetery, Neuville-Vitasse Pas-de-Calais, grave IB 49. His name is also recorded on the war memorial at Great Bedwyn churchyard, and the Southampton cenotaph. His widow lived at 1 Villiers Road, Shirley, in Southampton at the time of his death.

Private Harris 3rd May 1917

Charles Harris was the son of Charlotte Harris of Church Street in Little Bedwyn, and the husband of Edith Ellen Harris of 3 Council Houses in Chisbury.